![Lance Armstrong]()

As sprinter Oscar Pistorius, charged with murdering his girlfriend a year ago, takes the witness stand in self-defense, we're forced once again to do the impossible: separate truth from untruth.

Is he lying, as he describes shooting Reeva Steenkamp through a closed bathroom door? Or was he, as he says, legitimately frightened, and protecting her from an intruder?

To tell the truth, it's awful hard to catch a liar — or to even know if someone is telling the truth. The best estimate, based on hundreds of studies, is that people can spot a liar 54 percent of the time — a ratio that is perilously close to pure chance. But with lies being told every day — to abet financial skullduggery, everyday politics and of course everyday crime — the business of truth-telling ought to be booming.

After all, researchers say "Deception is a major aspect of social interaction; people admit to using it in 14 percent of emails, 27 percent of face-to-face interactions, and 37 percent of phone calls. 1

We're not worried about white lies, the grease of the gears of human relationships. We're worried about lies like the cascade of chicanery uttered by Bernie Madoff, the prince of Ponzi, who was convicted of a decades-long fraud that fried investors for an estimated $18 billion. We're worried about bigwigs like former president Bill Clinton, who lied when he said, "I did not have sex with that woman," and his predecessor Richard Nixon, who lamely (and laughably) proclaimed, "I am not a crook" as the Watergate scandal closed in.

And we're worried about athletes like Lance Armstrong, the erstwhile king of the Tour de France. After years of denials, he finally admitted that he, like many fellow bike racers, had been chemically enhanced.

Detection inflection

Truth is, after decades of work, the lie detection biz is floundering. "Reliable" techniques come and go. For decades, the instrument called the lie detector has been a mainstay of cop shows and station houses, but it's fallen from favor with the recognition that it can be beaten. Meanwhile, other supposed "tells" of untruth, such as avoiding eye contact or scratching certain parts of the face, are easily avoided by practiced liars.

"There is a huge literature of studies suggesting we are very poor" at lie detection, says Leanne ten Brinke, a post-doctoral fellow at the University of California-Berkeley school of business. "If I show you 10 videos and five show people lying and five show them telling the truth, your accuracy will be 50 percent. Flip a coin; don't bother watching the video. It's discouraging."

Professionals don't necessarily do much better, ten Brinke and colleague Stephen Porter wrote: 2 "even trained professional lie catchers often fail in detecting high-stakes lies."

ten Brinke and Porter added that when researchers showed police officers clips of people who, like the Canadian Michael White, had pleaded for help locating a spouse who had disappeared, "the officers could have flipped a coin and performed as well." Courts later ruled that White and many of the other "pleaders" had murdered the "vanished" person.

Lying: Why so convincing?

"Deception is a very complex human behavior and in spite of years of pondering over how to spot a lie, we humans, are not very good at this task," according to Victoria Rubin, assistant professor of information and media studies at the University of Western Ontario, London, Canada. Her email continued, "Computer programs can bring systematic ways of looking for what might give away a lie, but there is no simple solution. There is no real consensus among researchers in the field about what these best predictors of deception might be."

One reason for the difficulty, Aldert Vrij wrote in email, is that "People are good liars because they have a lot of practice, and practice makes skill." Vrij, a professor of applied social psychology at the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom, added that, "People lie every day (many white lies but also more serious lies) and children are instructed to lie (white lies) by their parents from a very early age (‘pretend you like the present grandma gave you')."

Liars notice if listeners swallow their spiel, "and people can learn from accurate feedback," says Vrij.

So what do we know about deception detection? What seems to work, and when? As we survey the human quest to ferret out lies, we'll focus on psychological tests, computer analysis of text and video, and advanced interrogation techniques.

Naturally selected?

You might think we humans have an advantage, since the ability to detect lies would seem essential enough to be favored by evolution. "We thought natural selection would promote this ability," ten Brink says, "and we also thought that for lie detection to be accurate and adaptive, it did not necessarily need to be conscious; you don't need alarm bells going off in your head, it could be subtle, so when you hear someone speak, you don't really trust them, don't feel like you want to lend them money or go on a second date."

To test that premise, ten Brinke and colleagues looked for implicit associations — concepts that are triggered by exposure to something in the environment. For example, if you harbor stereotypical feelings about green people, after seeing a photo of a green person, you would be more likely to understand, choose or recognize words that express your discriminatory feelings, like"bad,""nasty" or "untrustworthy."

In two studies, the conscious ability to distinguish truth from fiction was no better than chance, ten Brinke says, but "people responded faster to ‘truth' words after they saw a truthful video, and to ‘lie' words after they saw a lying video. This suggests that the unconscious mind does discriminate."

The "moral is that we might be better lie detectors than we thought, but the ability does not live in our conscious mind," ten Brinke said. The study might support a tactic of "going with your gut," but the false confessions uncovered by DNA tests show that this attitude among police investigators has put innocent people in prison. "I'm very unclear about the implication," says ten Brinke. "This does create a new interesting perspective on humans as lie detectors and opens a bunch of potential avenues. Can we look at the behavioral reaction of the receiver of a message to determine something about the veracity of the sender?"

How high are the stakes?

Many studies of lie detection are criticized because the subjects are, too often, college students who are asked to lie about trivialities. Critics question the realism of that setup, and argue that, lacking sufficient emotional stress, subjects fail to reveal the "tells" that often accompany high-stakes, real-world lies.

"The behavioral cues to deception tend to be quite subtle, especially when the lie is not high-stakes," ten Brinke told us. "When students come to the lab and tell a lie about their summer vacation, that's not high stakes. Unless it means a lot to you, you are not worried about being caught and might not leak any clues."

To deception researchers, "leak” means to unintentionally reveal a telltale sign of lying.

While researching her dissertation, ten Brinke focused on high stakes liars by studying videos of people who had issued a televised plea for help finding a loved one. Half of the 78 cases were genuine. In the other half, the pleader was later found to have murdered the disappeared person.

The pleader videos contained "pretty clear cues to deception," ten Brinke told us. "Deceivers smiled more; that's a very unlikely emotion for someone who's genuinely disturbed. They were unable to replicate genuine sadness in the face. There are muscles that are very difficult to control, so they were not able to pull off that look of sadness, particularly in the forehead."

Still, the tells were difficult to catch in real time, she adds. "My study was frame by frame, a very exhaustive, expensive analysis." Working in real time is "a very difficult task" so "videotaping is always recommended. The cognitive load [mental work] for the lie detector is incredibly high, especially if you are in conversation, and looking for an appropriate question, and examining the speech pattern and body language all at once."

The face, she says, is "an incredibly valuable cue to deception if you know what to look for; it can tell you a ton of interesting information."

Ken Lay was CEO of Enron Corporation, an energy firm that collapsed in scandal in 2001 in what was then the largest bankruptcy in American history. Lay is shown listening to a question outside of the U.S. Courthouse in Houston after the close of his bank fraud trial May 23, 2006 in Houston, Texas. After being convicted of 10 counts of fraud, conspiracy and making false statements, Lay died on July 5, 2006.

The interview

Much of the focus in criminal deception detection today concerns the interrogator, not the subject. One goal is to increase the subject's “cognitive load" (need to think fast) during interrogation. One way to do this, Vrij says, is to ask people to recall the event in reverse order. "‘You said you went for lunch with your friend. Tell me in detail what happened in the restaurant [working backward] from when you and your friend left the restaurant?'"

With cooperative witnesses, Vrij wrote us, reverse order recall often results in new information, but liars "will attempt to say again what they said when asked in normal order.

This is difficult to do and may lead to contradictions. Also, because liars focus on repetition, it is unlikely to result in new information."

Indeed, Vrij says, finding lies "Is all in the questioning. Through good interview techniques, deception may become apparent, but poor interview techniques are unlikely to elicit cues."

For example:

- Passive or general questions, like "Tell me in detail all that happened,""give liars the opportunity to report their planned lie," Vrij says.

- Leading or suggestive questions, like "Did you take the money?" can cause symptoms of nervousness among liars and innocents alike.

(Scientists interested in interrogations 3 have tried to evaluate the ability of various techniques to uncover lies. More recently, sparked by capital-case confessions that were later proven false by DNA evidence, researchers have tried to identify techniques that coerce the innocent to confess. One key offender: interrogators who falsely claim to have incriminating evidence.)

Computer vision? ***

It’s the computer age.

So what can our digital slaves add to the enigma that is deception detection? Computers may lend a hand in analyzing the highly expressive human face, which nonetheless baffles most human efforts to detect lies. Aware that slackers seeking disability benefits often lie to doctors about pain, Kang Lee, at the Institute of Child Study at the University of Toronto, asked subjects to show real or faked pain. "The question was, when humans express a genuine emotion, do they use one group of muscles, and when they express fake emotions, do they use a different group of muscles?" Lee explained. (The experimenters immersed subjects' hands in cold water, which Lee says is "very painful, but safe.")

Because pain is a universal experience, "We are very well versed in faking pain," Lee says, which makes the task tough for deception detectors. When Lee trained people to analyze the videos, their accuracy rose from chance to 56 percent. "It was very poor, and that's been found before," he says.

The old-fashioned "lie detectors" measure sweating, respiration and heart rate, which indicate heightened "arousal" caused by the state of deception — or something else. Critics say the detectors are far from foolproof. Here, Igor Matovic, member of the Slovak Parliament, demonstrates his recent lie-detector test during a press conference on February 23, 2012, in Bratislava, Slovakia.

By using machine learning, Lee, working with Marnie Bartlett of the University of California, San Diego, taught computers to detect deception with 82 percent accuracy. "That's a big leap forward, and it tells us there are signs in the facial expression that can tell us if they faking or are experiencing pain for real," Lee says.

Frame-by-frame video analysis revealed that real and faked pain have different expression. "When faking, the mouth opens with a very regular, rhythmic dynamic," Lee says, which does not appear with real pain.

That subtle distinction shows the advantages of computer vision, he says. The computer "can remember frame by frame; our cognitive system has a low capacity, we can't remember these dynamics, and the mouth is only one part, we also have to look at the eyes, the nose the cheeks and the words. That is lot of information to compute concurrently."

The words have it!

In a recent study, Lynn Van Swol, an associate professor of communications arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, found that lies were easier to detect by computer chat than from watching a video.

Why? "There may be just too much to analyze in a video," says Van Swol, "and that takes away from probably one of the best indications, what the person is saying, and putting it in context."

The context includes common sense and knowledge of the world. Say, while trying to decide if someone was truthful, you asked about favorite pastimes and were told, "I like to write poetry.""You might think, how many people could truthfully give that response?" says Van Swol, "rather than looking at whether his eye is twitching or he's scratching his chin." Poetry is a scarce avocation, so that answer is a possible — but hardly conclusive — tell of deception.

Trust a computer?

Computers can also analyze text, looking "for a pattern of objectively-observed predictors of deception," as Rubin wrote to us. For example, if it's true that liars try to avoid the first-person pronouns "I" and "we," a computer can quickly examine text to look for an abnormally low number of first-person pronouns. The pronoun theory is debated, and Rubin agrees that any one indicator is not definitive, but rather "should contribute towards the overall decision making – is this given text truth or a lie?"

Computers, she notes, are fast, consistent and obedient. They have "a certain type of objectivity, assuming the programmer instructs the program based on scientific consensus, and not his or her personal opinions. Computer programs can be trained to look through large volumes of data, observe patterns, and make certain conclusions on which to base their further decisions."

Using this so-called "machine learning, Rubin and colleagues created software that detected 65 percent of lies, somewhat better than the 50- to 63-percent performance from people in the same study.4

What might account for the slight advantage for computers? People, Rubin wrote, "are not necessarily objective, nor systematic, nor do we know what exactly to look for to spot a lie. We quite often rely on intuition. We are subjective and have emotions; for instance, liking an idea might help us validate it. We might misinterpret cues. We multi-task as we read — we need to understand what is said and perhaps think how it's phrased, make connections to what we already know, remember what we've read in order to evaluate its veracity. Ultimately, the task is cognitively taxing and we are just human."

But being human has advantages, Rubin adds. We have "the powers of true comprehension of the situation in a life context and the ability to see the big picture, to reason and be self-aware. Say, someone is stating the opposite of what's obviously true. A human knows to interpret it as sarcasm and how to react to it and what it actually means."

Between crime, sports and politics, the need to detect deception is not fading away. And Rubin reminds us of another playground for deceit. "We communicate and get our information via computer and mobile devices. We are unsuspecting, truth-biased [tending to believe what we read, in other words], and potentially vulnerable to online predators, spammers, scammers, and opportunists with malevolent deceptive intentions."

UP NEXT: 5 ways to tell if someone is cheating on you

Join the conversation about this story »

NOW WATCH: How To Know If Someone Is Lying To You

Fights about money aren't uncommon in marriage and according to at least one survey, 70% of couples argue over financial matters from time to time.

Fights about money aren't uncommon in marriage and according to at least one survey, 70% of couples argue over financial matters from time to time.

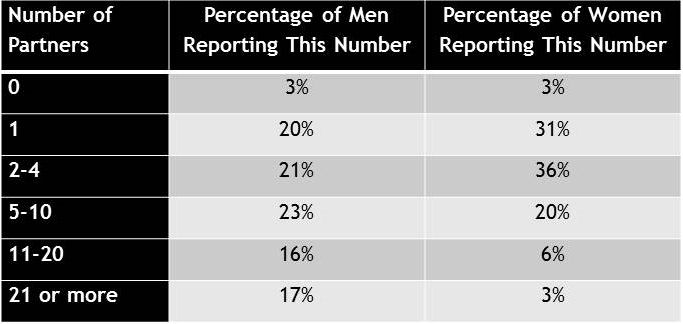

Every Friday on the blog, I answer people’s questions about sex, love, and relationships. This week’s question comes from a reader who wanted to know:

Every Friday on the blog, I answer people’s questions about sex, love, and relationships. This week’s question comes from a reader who wanted to know:

"Men are expected to make a lot of money," says Seabrook. "And women are expected to value men who make lots of money."

"Men are expected to make a lot of money," says Seabrook. "And women are expected to value men who make lots of money."

Resnic became obsessed with answering that question: He read everything he could find about condoms at his local public library in Miami. He learned how latex condoms are made (by dipping phallic molds into vats of liquid latex, which is peeled off after it dries), and how they are regulated (the Food and Drug Administration considers condoms medical devices and dictates how they are manufactured and labeled).

Resnic became obsessed with answering that question: He read everything he could find about condoms at his local public library in Miami. He learned how latex condoms are made (by dipping phallic molds into vats of liquid latex, which is peeled off after it dries), and how they are regulated (the Food and Drug Administration considers condoms medical devices and dictates how they are manufactured and labeled). I met Resnic for lunch in Los Angeles last September and was struck by his intensity all these years later. To illustrate his astonishment at what he’d learned about condoms, he gestured at the salt and pepper shakers and bottle of olive oil between us. “Everything on this table—these jars, these nozzles—every year they come out with a better product,” he said.

I met Resnic for lunch in Los Angeles last September and was struck by his intensity all these years later. To illustrate his astonishment at what he’d learned about condoms, he gestured at the salt and pepper shakers and bottle of olive oil between us. “Everything on this table—these jars, these nozzles—every year they come out with a better product,” he said. Resnic is not the only one who has been trying to build a better condom.

Resnic is not the only one who has been trying to build a better condom.

Condom compliance—the ability and willingness to use condoms consistently and correctly—has always been a big problem. The Gates Foundation knows it, and so do all of us who’ve decided to just chance it during sex, even when the Trojan is sitting right there on our bedside table. A more enjoyable condom—a condom that people want to use—could significantly reduce STIs and unwanted pregnancies, both in America and abroad. So why hasn’t the always unpopular latex condom ever faced any serious competition in the condom aisle? Why, after all these years, is latex still king?

Condom compliance—the ability and willingness to use condoms consistently and correctly—has always been a big problem. The Gates Foundation knows it, and so do all of us who’ve decided to just chance it during sex, even when the Trojan is sitting right there on our bedside table. A more enjoyable condom—a condom that people want to use—could significantly reduce STIs and unwanted pregnancies, both in America and abroad. So why hasn’t the always unpopular latex condom ever faced any serious competition in the condom aisle? Why, after all these years, is latex still king? Their first attempt at advocacy didn’t go over well. “

Their first attempt at advocacy didn’t go over well. “ Today, the idea that gay men should wear condoms to protect themselves from HIV is a given—although

Today, the idea that gay men should wear condoms to protect themselves from HIV is a given—although  As the safe-sex message spread from Greenwich Village to the rest of the country, the nuance of How to Have Sex in an Epidemic got lost. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, the Reagan appointee legendary for speaking frankly about AIDS and sex in spite of his evangelical background, began talking about condoms in 1986. In his “

As the safe-sex message spread from Greenwich Village to the rest of the country, the nuance of How to Have Sex in an Epidemic got lost. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, the Reagan appointee legendary for speaking frankly about AIDS and sex in spite of his evangelical background, began talking about condoms in 1986. In his “ Most of the condoms sold in the mid-’80s were, as they are now, latex. But another category of condoms experienced sales growth between 1986 and 1988, according to that American Journal of Public Health study: Lambskin condoms, which How to Have Sex in an Epidemic championed as “thin, sensitive and durable.” Even Anne, the New York Times’ attractive widow, ended up buying lambskin condoms.

Most of the condoms sold in the mid-’80s were, as they are now, latex. But another category of condoms experienced sales growth between 1986 and 1988, according to that American Journal of Public Health study: Lambskin condoms, which How to Have Sex in an Epidemic championed as “thin, sensitive and durable.” Even Anne, the New York Times’ attractive widow, ended up buying lambskin condoms.

“The effect was comparable to 50 postejaculatory strokes, an unrealistic event for most people,” the lead author conceded later. But just in case 50 postejaculatory strokes were too few, a team at the University of Calgary fit each virus-filled condom over an 8-inch mechanical vibrator and lowered the device, vibrating, into a saline-filled beaker

“The effect was comparable to 50 postejaculatory strokes, an unrealistic event for most people,” the lead author conceded later. But just in case 50 postejaculatory strokes were too few, a team at the University of Calgary fit each virus-filled condom over an 8-inch mechanical vibrator and lowered the device, vibrating, into a saline-filled beaker  That’s because, in 1991, the FDA began requiring lambskin condoms to carry a label stating, “Not to be used for prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). To help reduce the risk of catching or spreading many STDs, use only latex condoms.”

That’s because, in 1991, the FDA began requiring lambskin condoms to carry a label stating, “Not to be used for prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). To help reduce the risk of catching or spreading many STDs, use only latex condoms.”

In a small laboratory in an office park in northern San Diego filled with Mason jars, a Vitamix blender, and glass phalluses, Gates Foundation grantee Mark McGlothlin showed me a few prototypes of his reconstituted collagen condom. McGlothlin is trying to develop a condom that marries the sensation of lambskin with the security of latex. His idea is to take common agricultural waste products, like cow tendons and fish skins, break them down to pure collagen, blend them with plasticizers, and turn the resulting soup into film.

In a small laboratory in an office park in northern San Diego filled with Mason jars, a Vitamix blender, and glass phalluses, Gates Foundation grantee Mark McGlothlin showed me a few prototypes of his reconstituted collagen condom. McGlothlin is trying to develop a condom that marries the sensation of lambskin with the security of latex. His idea is to take common agricultural waste products, like cow tendons and fish skins, break them down to pure collagen, blend them with plasticizers, and turn the resulting soup into film. Even though the FDA had officially already cleared the condom to be sold with a label claiming that it was effective against pregnancy and STIs, it got cold feet at the last minute. After the first packages of the Avanti condom had already been printed, the agency made LIG replace the original labeling with a label that stated that the condom’s effectiveness was uncertain and that it was intended only for latex-sensitive users—not exactly the kind of label that makes boxes fly off shelves. “We let it go on the market with interim labeling very carefully," Lillian Yin, then the director of the gynecological division of the FDA’s office of Device Evaluation, told a reporter for the newsletter AIDS Alert at the time. “We are not encouraging it for the general public.”

Even though the FDA had officially already cleared the condom to be sold with a label claiming that it was effective against pregnancy and STIs, it got cold feet at the last minute. After the first packages of the Avanti condom had already been printed, the agency made LIG replace the original labeling with a label that stated that the condom’s effectiveness was uncertain and that it was intended only for latex-sensitive users—not exactly the kind of label that makes boxes fly off shelves. “We let it go on the market with interim labeling very carefully," Lillian Yin, then the director of the gynecological division of the FDA’s office of Device Evaluation, told a reporter for the newsletter AIDS Alert at the time. “We are not encouraging it for the general public.”

The FDA was given the authority to impose standards on condoms with the passage of the Medical Device Regulation Act of 1976. Understandably, it spent the next decade focusing on more consequential, complex medical devices—pacemakers, ventilators, that sort of thing. So when, in 1986, the surgeon general began promoting condoms to prevent AIDS, the FDA was caught off guard. “All the division chiefs got together one Friday afternoon and said, ‘What do we know about condoms? What do we know about latex?’ We knew nothing,” says Don Marlowe, the former director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, the branch that is charged with regulating condoms.

The FDA was given the authority to impose standards on condoms with the passage of the Medical Device Regulation Act of 1976. Understandably, it spent the next decade focusing on more consequential, complex medical devices—pacemakers, ventilators, that sort of thing. So when, in 1986, the surgeon general began promoting condoms to prevent AIDS, the FDA was caught off guard. “All the division chiefs got together one Friday afternoon and said, ‘What do we know about condoms? What do we know about latex?’ We knew nothing,” says Don Marlowe, the former director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, the branch that is charged with regulating condoms. At the time, condom companies were supposed to adhere to a standard created by a private, not-for-profit standards development organization called American Society for Testing and Materials, whose rules hadn’t changed much since the 1940s. The ASTM condom subcommittee was, back then, populated mostly by scientists and sales representatives from condom companies, all of whom had an interest in keeping the standard favorable to their bottom line. When, in the wake of the surgeon general’s call to action, FDA representatives joined the ASTM subcommittee in the late ’80s, they came with an implicit threat. Since the FDA had the power to change labeling and recall products, the agency “became the 800-pound gorilla in the room,” says Marlowe.

At the time, condom companies were supposed to adhere to a standard created by a private, not-for-profit standards development organization called American Society for Testing and Materials, whose rules hadn’t changed much since the 1940s. The ASTM condom subcommittee was, back then, populated mostly by scientists and sales representatives from condom companies, all of whom had an interest in keeping the standard favorable to their bottom line. When, in the wake of the surgeon general’s call to action, FDA representatives joined the ASTM subcommittee in the late ’80s, they came with an implicit threat. Since the FDA had the power to change labeling and recall products, the agency “became the 800-pound gorilla in the room,” says Marlowe. However, I was unable to find a single entry related to TheyFit in the

However, I was unable to find a single entry related to TheyFit in the

.jpg)

There to cheer Bündchen on was her husband of six years and father of her two children, NFL quarterback Tom Brady.

There to cheer Bündchen on was her husband of six years and father of her two children, NFL quarterback Tom Brady. Just look how proud he is!

Just look how proud he is! After the show, Brady expressed amazement with his wife to his nearly 3.2 million

After the show, Brady expressed amazement with his wife to his nearly 3.2 million